- Home

- Alden Moffatt

Magic Wings Page 3

Magic Wings Read online

Page 3

I watched that June day as Eddie launched his glider. His tight control over the wing hid the effects of the turbulence from my untrained eye. I was watching the levelness of his wing for hints about the air. I later found out that I should have been watching the position of the pilot, how far he had to lean from side to side, how far he had to adjust his weight to keep the glider level, and how frequently he had to make weight corrections. A hang glider is controlled by shifting ones weight and thereby changing the center of gravity.

There are a million little movements that go into flying in a straight line as turbulence and thermals rock the glider from side to side. When the turbulence is extreme, a pilot may have to throw his whole body weight to one wing with his arms extended from one corner of the control bar. If I had noticed Eddie with his body all underneath one wing of his glider and him stretching toward the wing tip with his feet, I wouldn’t have flown that day. Instead, all I saw was the peaceful , butterfly-like glide of his level wing moving romantically away from the launch area and into the clear, blue sky. He rose constantly as he flew in a wide ark and then he disappeared around a corner.

Zeek was there. It was fairly calm on the launch and quite warm. “This might be a nice flight for you”, he said as he watched Eddie rising effortlessly.

Zeek had tutored me about hang gliding many times. He was one of the very best local pilots, I thought. But he had very little understanding of other people’s limitations, probably because he didn’t have any, nor had he for quite some time.

He sat under my wing in the shade, waiting for me to launch. I guess it was for moral support, because he didn’t mention anything about south winds or turbulence. Instead he was talking about his wife who was in Alaska at the time, his house that he was moving out of, and his dog barking, chained to the truck.

Soon a little puff of wind came twittering up the hill. I ran straight toward it. Once the combination of my running speed and the speed of the wind added up to fifteen miles an hour, the glider lifted up and carried me off the ground with it.

I came across the first turbulence after I had cleared some tree tops and had stuffed my legs into my harness. The turbulence threw me toward the mountainside. I corrected the unwanted turn and continued onward. Then another bump threw me the other way. And another. Soon my glider was waving back and fourth in the wind nearly out of control. I was also climbing at a furious rate.

My teeth were locked together, grinding away at each other, and my hands were locked tight on the control bar. The ground rushed away and as it did the glider bucked and lurched like a bull ride in a rodeo. My feet kicked the sail, then the flying wires. I worried that I would damage the glider. My helmet, which I had purchased at the Salvation Army for a couple of bucks, didn’t fit very well and rattled around on my head, sometimes covering one eye.

Over the mountain top, a down draft caught me and I was flying straight down toward the ground, then with equal force it turned into an up draft. The sail yanked at the control bar which in turn yanked at my arms. My stomach muscles clenched and my whole body became ridged. The roller coaster ride was not making me sick, but what if there was a point where I couldn’t handle it anymore? What would it be like to be sick right now, I thought? That would certainly make matters worse.

For an hour I tried to hold on, not sure if I really wanted to fly after all. This was what Zeek called a “nice flight” eh? I would hate to be there for a bad one. I held on that day because all my flights to that point had been hair raising for me. If you watched them from the ground, they all looked peaceful enough, I suppose. But flying was a traumatic experience for me and though I was compelled to pursue wings and sky, there had been no peace there for me. What if it was always turbulent when there was lift enough to hold a glider up? The thought made me cringe. How could I ever enjoy hang gliding if the air always intimidated me.

When I could take no more bumps, I headed for the valley floor to land. Once I was away from the mountain side, the air smoothed. But I was exhausted and still clenching the control bar. My body was ridged and my mind was petrified. How many times would I feel frightened to death before I would finally say, “No more! I Quit!”

But I kept coming back.

Family

Ah, Woodrat! How many days of my life did I spend on that mountain? Sometimes the wind would blow the wrong direction all day and no one could fly. It was usually hot there on the top launch and when it was hot it was always way too sunny. My face and arms were always sunburned. A gravel quarry operation had removed every single tree near the launch. There was no place to sit in the shade but under a glider. Pilots did not want to set up their gliders too early either, because the suns rays ruined their sail material. As it was, a glider would only last a few years, so everyone protected their gliders skin at the expense of their own. Everyone had a sunburn except those with the darkest of skin tones. I was the reddest flier of all.

During the long hours of waiting for the wind gods to cooperate, I got to meet the other pilots. We’d talk about equipment, or the weather, or our wives at home (or wherever they were).

The narrower the sail was from front to back, the better the glider’s performance, but the harder it was to fly. The main thing needed for flight is an air foil. The long wing span gliders with the narrow wings and with long airfoils have a better glide to sink ratio than do the shorter, more triangular hang gliders. But those high performance gliders are more dangerous to beginning pilots because they have delayed responses. The wider gliders with the shorter wings float better and are more forgiving.

I needed all the forgiveness I could get, according to Duke, a pilot I had just met, but who had watched me since my first Woodrat Mountain flight.

Stormy and Tweedie were also there a lot and with Zeek and Eddie, they were the people I saw most often hang gliding.

Tweedie was the local celebrity pilot, the one who had flown since the beginning days of hang gliding in the nineteen-seventies. He had flown almost every type of personal glider ever invented. He always wore a skin tight lycra suit to fly in that left only a view of his nose and eyes.

“Tweedie”, Zeek teased, “ sells his equipment about every two years. He gets spooked and swears he’ll never fly again. A couple of years ago he got to 20,000 feet and it took him a long time to come back down. He said he had a dream that night that he was stuck up in space forever. The next day he sold his wing and everything else he glided with for a fraction of what he bought it for. I wish I’d been the one to grab it. A few months later he bought all new equipment. He has a trauma about every year. If you want some great equipment for cheap, you have to convince Tweedie to buy the stuff you want. Pretty soon he’ll dump it and you just have to be there when he gives it all away. Tweedie’s a little eccentric”, confided Zeek. “But he’s the best pilot around. He doesn’t fly much around here anymore, so you won’t see him too much. Since that 20,000 foot flight, he likes to fly close to the ground and the best place to do that is along the coastal cliffs.”

“Yeah. We call him the coastal pilot”, said Stormy. “That’s sort of a nick name. If you want to stick a thorn in Tweedie’s side, just call him ‘coastal boy’.”

Stormy was the best hang glider lander I’d ever watched. I loved the way he carved a path around a tall pine on the edge of the landing field and swoop down to land on his feet right next to the car. Stormy had a style about him that was his signature. He wrote his name in the air when he flew. For him, flight was more of a self expression than a competition. He didn’t care how high he went or how fast. He just needed to do a little artwork on the sky. That’s why he was there.

Tweedie, on the other hand, had been fiercely competitive from time to time in his life and had done well in any competition he had participated in.

Stormy was a quiet character who would give advice if asked but usually sat by himself.

Tweedie was an aging party animal who talked about flying on LSD or by moonlight.

Stormy

was quiet but tough. I was surprised to watch him belt down a beer or two before a flight.

Everyone I met hang gliding had an excessive personality. They were moody eccentric people.

Zeek sometimes talked about being a doctor in some war and according to him, he was the only one who could do the job so he could talk to the captains or generals any way he wanted to. “What were they going to do? Fire me?” he said. In his stories he was the most useful, most proficient, the most experienced. In the air he was an awesome pilot. There was no doubt about his piloting skills. He was there to prove that he was the best, the bravest, the smartest.

Eddie said to me one day when Zeek wasn’t around, ”That guy pisses me off. Every time we fly together he goes cross country. It’ll be a shitty day and I’m about to land after capping out at 5000 feet for two hours. Then all of a sudden the idiot on the CB radio says he’s going for the next ridge over. You know, you shouldn’t go cross country around here unless you’re at 7000 feet or more. Anyway, Zeek get’s a bump here and there and makes it to some little field ten miles away that’s a pain in the ass to drive to, and he wants me to come pick him up. Every time we fly he does something stupid like that. I wanna go home and have a beer with Tiki and now I gotta drive for an extra hour. He’s a pain in the ass.”

Duke was a short, skinny, middle aged guy. Stormy said Duke always had to have a plan before he flew. “Duke never goes anywhere on the spur of the moment. By God, he plans to do something a week in advance and the weather just better cooperate. So what if the wind’s blowing the wrong way or it’s raining. One day he dragged me out to Woodrat and the south wind was howling and storm clouds were all over. You could see where the rain was coming down in buckets in the distance and we sat up there all day getting wind dried until it started raining and we went home, just because Duke had taken a day off work because he said it was going to be great that day when he made the plan a week before.”

And Tweedie said about Zeeks dog, while he wasn’t looking: “ You know, you gotta watch that yappy piece of shit when you launch. He’ll grab your heals when you’re running with your glider and hang on til he’s airborne and almost making you into a crash statistic.”

Zeek moved away a year after I took my first flight at Woodrat, but until then I usually traveled to launch with him because we both lived at the same end of the Rogue Valley. Now and then, his wife would come along to drive his truck down the mountain. Usually Zeek’s dog would come along. I tried to like the dog.

One day, when we were half way up the mountain a horrible stink fumed up from the canopy on the truck bed and the dog had unloaded his morning chow. Zeek stopped, jumped out of the truck and put on a latex glove. He grabbed the soft, steaming poop off of my glider harness and heaved it into some bushes.

“Glad to see you’re prepared”, I said.

“Happens all the time”, said Zeek. “Eddie’s been flakin’ out on hang gliding. I called him this morning and left a message and he doesn’t call back. I called yesterday too. He always has some excuse. I think Tiki’s been on his case, whining about how he’s gonna kill himself and leave her with no money and no one to fix the house. If I had a woman like that I’d dump her in no time. That’s what happened to Stormy. But Stormy was smart enough to tell his wife to go suck an egg. Eddie’s pussy whipped. You otta see that couple chortle and growl. It’s enough to make you wanna pop your cookies. Bad dog Fido!” he said as he threw the glove off the road. The glove landed in a tree branch and made a phallic sign with the middle finger.

When Zeek’s wife was with us, Zeek was subdued. She and Tiki were good friends.

Baking in the sun at Woodrat, Duke said “I hate this place. The only reason all these guys come here is because they’re too scared to fly anywhere else. There’s lots of places to fly. This mountain is boring to look at and it hardly ever gets really great.”

“I should have been born in Hawaii”, said Tweedie. “You could have hula girls on the beach when you landed. Imagine flying over the warm waves and having tourists treat you like a rock star. Don’t listen to this guy,” he pointed at Duke. I love to go other places. Duke’s the one who’s boring. He’d just rather have a sled ride a hundred miles from here than a record flight on the home turf. You’ve got to come here a bunch of times and you’ll agree, Woodrat is a great place to fly.”

“What are you talking about coastal boy”, Duke teased. “We hardly ever see you around here anymore. Going for some records over those cold, north coast beaches? I bet you never get a hundred feet over the cliffs.” Duke turned to me,” And every time I went to the coast to fly with Tweedie the wind was blowing the wrong way. That’s a big three hour drive each way and you just sit there and look at the waves.”

Stormy, Eddie, Tweedie, Duke and Zeek had flown together for a many, many years. They chattered away like family. I was the new pilot and I mostly kept my mouth shut and listened. The wind would blow, sometimes, up the west slope, and sometimes we’d all take to the air.

I always ended up landing first. There was no place to get out of the sun in the landing area, unless there was a truck parked there. All the shade trees were surrounded by cows standing in ankle deep manure and dust. During the heat of summer the truck would be filled with flies. I sat in the truck for many hours at the landing area, watching my fellow pilots fly up and beyond where I could see them. They turned into specks and often disappeared into the blue.

Herd Peak

When Zeek moved away, Eddie stopped flying. I tried to get him to fly with me several times, but he always said he was busy, so I became dismal. I could not learn to fly without Zeek, Eddie and Badger I thought. There was no one to help me, no one that I trusted anyway.

But Duke called me on a cloudy morning. “I looked at all the weather predictions and today’s going to be good at Herd Peak. You’ve been flying for a while at Woodrat and now I think you’re ready.”

His voice chilled me to the bone. I was barely controlling my panic each time I drove to Woodrat Mountain and I was barely getting used to flying there. I knew the lay of the land at Woodrat and what I had to look out for, to have a sled ride quickly from the top to the bottom anyway. I knew I could usually land there safely. Now Duke, who I barely knew, wanted me to do something new. The thought was unbearably.

He was persistent though. “You can’t just keep going back to the same place and call yourself a pilot. There are a lot of new things to try. Herd is way different than anywhere you’ve glided before. Don’t be like all those sissies who get themselves a bumper sticker and tell their friends they’re an expert. This is gonna be cool. I swear, you’re gonna do fine, and you’re gonna like it too,” Duke insisted.

I was squirming, looking for a way out.

“Come on,” he pleaded. “I’ve been planning this trip for a month now. I got a day off work. We gotta go!”

“Well”, I said, “I guess I could keep you company, but I don’t guarantee I’ll fly.”

“Great! Lily’ll make sandwiches. We’ll have a picnic. I’ll be there in an hour.” He hung up.

Duke showed up with his wife a little late, giving me time to think about what I was going to do for a little bit longer. The time waiting for him went by slowly.

Then he pulled up the driveway. Someone else was in the car with Duke and Lily. They had brought along a spectator, a friend of theirs who was over eager to watch “some daredevils jump off a mountain.” His name was Bonzo.

It was an hour and a half drive to the site, ‘the site of the catastrophe’, I anticipated. When we were getting close and had turned off on a maze of dirt roads and the roads had gotten smaller and smaller until they were only tracks in the dust, I began to feel a real sense of terror setting in.

My glider was on the roof of the car and everything I needed to fly with was inside. Why hadn’t I conveniently forgotten something; a crucial strap, my battens, something.

Lily was calmly talking about her quilting club and her job at the clinic

. “They made me be president of the club because no one else wanted to do the job. So I have to arrange all the quilt shows and write for the news letter.” She was knitting a small square for her quilt while we road along the bumpy path.

“That must be very satisfying for you”, I said, hiding my inner world of anxiety.

“Hey man,”said Bonzo, who was drinking a beer and enjoying himself. “We almost there? I can’t wait to see you two dudes jump! I’ve never seen anyone fly. Wow. This is going to be way cool.”

“The landing area is right up ahead,” said Duke, who stopped the car in front of a locked gate. “Hope you brought the key, Hun,” he said to Lily. The dust our car had left behind now blew over us. Duke coughed. ”See, it’s a lot different here than it is at home. It’s sunny, a beautiful puffy cloud day and the wind’s blowing perfect.” The dust cleared and he opened the gate.

We pulled forward a hundred yards to where a view of the mountains opened up. Fourteen thousand foot Mount Shasta was on one side and Duke pointed to Herd Peak. “That’s the spot, right where the road wraps around the ridge. We launch from there.” The road he was talking about looked like a slender thread way up on a huge mountain. It looked like a scratch on an image on a piece of film.

I tried to act like I was thrilled to be there. “Wow, This is great,” I said. “How long does it take to get up there?” I said hoping it would take forever.

“About an hour”, said Duke, “but we’re lucky today. Lily’s driving so we don’t have to go back up there to get the car after we fly.” Turning his attention to the landing area, he said, “Damn. These bushes take over everything. This LZ was a lot bigger last time I was here.” He was talking about sage brush and he wandered around pulling some of it out. The bigger bushes were there to stay though, as were a few little juniper trees which had grown into a considerable landing hazard. “I used to glide in here with plenty of room, but now were going to have to set up our landing approaches way out over the brush field and try to get down to within a foot or two of the treetops so we don’t over-shoot the clearing. But we can do this,” he tried to convince himself. “He turned his head to look east and said to me, “What do you think of the cliffs?”

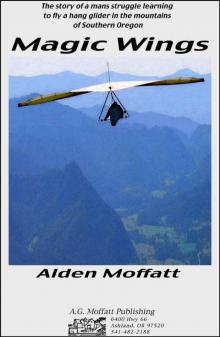

Magic Wings

Magic Wings