- Home

- Alden Moffatt

Magic Wings Page 6

Magic Wings Read online

Page 6

“I’d do that too,” said Duke. But everywhere where there’s a good climate, there are too many people, and they all get in the way of what you want to do, just like the weather. Maybe a man’s only supposed to get just so much done here on this planet before it’s time to go.

“Yeah, I know what you mean. ChiChi has been reading some supposed spiritual elevator called ‘The Power of Now’. I’m writing a book called ‘The Power of NO’. Or maybe I’ll call it ‘The Power of Never!’. I wanna do this and I wanna do that and the answer’s always NO. And then the clock runs out. I thought there would be plenty of time for everything when I was twenty. Now I can’t even get the stuff done that needs to be done, let alone the fun stuff,” I said.

“How do you think you got into this situation?” asked Duke, obviously pretending to be my psychoanalyst.

“I don’t know. ChiChi, how do you think I got into this situation?” I inquired, aiming my question at the other side of the large living room.

The girls were ignoring us, talking about gardening, cooking and yoga, all at once. They were giggling and their lack of interest in me and Duke was intentional.

“I’m gonna sell my house and move into the country,” said Duke. “I want a two car garage with one big room upstairs to live in. I want it all made out of something that never needs maintenance. In my garage I want a kayak, two gliders and a wind surfer.”

“I could live a lot simpler if someone wasn’t pushing me into acquiring and more acquiring,” I gestured that the ‘someone’ I was talking about was ChiChi.

“You know what I don’t understand,” said Duke. “How do all those people out there think they’re gonna take all that stuff with them when they die? There are so many people in this country who think they need to live in huge houses filled with crap. I know people who don’t admit to themselves that they’re going to die someday, even when they’re hauled off to a rest home. And they won’t admit they’re getting older either. I think if people would just take a close look at their situation, the world wouldn’t have to deal with all the crap they leave behind when they die.”

All of a sudden, across the room, ChiChi spoke to us. “My mother and grandmother both died recently and left us weeks of junk to sort through. I hope, when I die, I won’t be such a burden on my family.”

“Duke,” said Lily. “You act like nobody but you has a brain. You think that nobody is thinking about anything important except you.”

Then Lily and ChiChi turned back toward each other and started giggling quietly and gossiping again.

One after another, winter days went by and we all got perpetually older.

The Gravel Quarry

When the great thermaling conditions at Woodrat Mountain were discovered in the early 80s pilots launched on a brushy area facing west on a ridge 2300 feet above the Applegate River Valley. Gliders back then had to be carried a ways from the end of a BLM logging road.

During the fall and winter of 2001, the government agency used the launch ridge as a gravel quarry for the third time, the end result of which was a large parking lot. With a lot of labor from Southern Oregon glider pilots, two world class launch slopes were smoothed and graveled there. But before the work was done, just two weeks before the annual fly-in that attracts pilots from all over the country, the most consistent and reliable launch area near my home was covered with huge, jagged boulders from dynamiting on the ridge.

During the winter I had not been able to fly because of consistent, bad weather. But when March came around, the northwest wind returned. That fair weather wind races up the Applegate River canyon and spreads out in a smooth layer as it slides across the wide Applegate Valley. The wind warms as it blows across the the valley’s checkerboard of farms. When the smooth, warm wind meets with the slopes of Woodrat Mountain and it has no where else to go but up, it is forced into a couple of funnel shaped gullies which concentrate thermal air from many miles away.

With the return of that fair weather wind, which happens only when the jet stream passes to the north of Oregon, I became anxious to try out my glider again. The glider had been sitting in our shop now for five months, under a tarp to protect it from the many leaks in the roof.

As I drove to the mountain top, I tried to relax , but I had seen the huge rock piles at the launch, so I was filled with apprehension. Would I even be able to get to a safe place to launch? Would it be possible to carry the set up gliders from what remained of the access road across the boulder mounds and onto the windward mountain face? I also wondered if I remembered everything I had learned during my first summer of altitude gliding, things that would keep me from making a mistake? What must the wind feel and sound like to assure me that I was not flying the glider into a stall? How heavy must I shift my weight in order to get the glider to turn? Will I get the glider into the right position to land safely? I decided not to take any chances that day. I would give myself plenty of leeway, even if it meant flying straight from the mountain to the landing area.

But the launch was going to be tricky. There was nothing I could do to make the launch situation safe. My stomach was tied in knots.

Stormy, who had flown for over ten years, was in the large cow pasture where I had done my very first high flight landing a year before. That flight had ended in a tree not far from where we now stood. The tree had subsequently been cut down by the land owner and was now a stack of firewood next to a stump. Stormy wasn’t sure why they had cut it. The tree surely couldn’t have been mortally wounded by my crash into it.

I hadn’t seen Stormy since the last October, when winter had closed us into our separate houses. We were both anxious to fly.

Now we looked carefully around the landing field. There were a few cows grazing that would be moving obstacles when we landed. The cows were in a far corner of the field, but the wind was coming from the far corner also, so we would have to set up for a landing over the parking area then glide down toward the cows hoping that we would stop before we reached them. The field was wide enough to handle the conditions that day, if the cows didn’t move up wind before we needed it.

I loaded my glider onto Stormy’s truck. Then we left the landing area behind and drove up the final eight miles of winding road to the gravel pit launch, high on the ridge top.

My heart sank as we arrived at the pit. The mounds of boulders were larger than I had remembered and the huge gravel grinder and a bulldozer were in our meager parking area. We stumbled around the bulldozer looking for a place to launch.

Loose boulders rolled easily on the steep slope. There was one small place where we could toss boulders aside and make a gravel path straight down, on the west slope, but it would be only ten feet long and it was going to take a huge effort to carry the gliders, set up, from a small flat area behind the bulldozer to that launch spot. Then, when we would run down that path with our gliders attempting to launch, there were uneven mounds of rock which could catch on our wing wires and catapult us down into sharp rocks below.

Wind was blowing straight up the hill at twelve miles an hour, which would be fine for a two or three step launch, which was all we would have room for. But the wind, being fairly strong, would make it harder to handle the gliders as we moved them across the rock piles and into launching position. To make matters worse, one of us would have to launch without any help. There would be no one to hold the second pilot’s wing wires to stabilize the launch, or even to help carry that glider to the launch path.

If the weather hadn’t been almost perfect that day, we probably would have gone home. Puffy cumulus clouds were forming, marking the tops of thermals rising up all across the mountain ridge. Those clouds drew outlines of the ridge onto the bright blue sky. Thermals usually break away from the ground along the highest terrain, where the rising air has no more warm Earth to cling to. Judging the wind and clouds, Stormy suggested that it would be a phenomenal flying day and would be worth the extra effort to get off the ground.

We had to make the lau

nch path.

After tossing aside many sharp boulders, we set up the gliders. Then it was time to launch. I, having had much less experience, would go first.

Stormy gripped my glider’s nose wires as we stumbled across the boulders to our make-shift launch area. Rocks rolled and the wind buffeted the glider around. I was hooked onto the glider as we shimmied, contouring across the mountain side.

Before I took my three steps down the short path we had cleared between boulders, I lifted the glider up a little higher than usual to keep the right wing from dragging across the rocks. I turned my head to one side, closed my eyes and grimaced, imagining what those rocks below launch would feel like if I was unfortunate enough to crash into them.

Then I turned my head to look down the hill. Trees below tossed in a bubble of hot air rising toward me. The brush below the launch started to wave in the wind. Then closer bushes rattled. Suddenly I was hit in the face by the updraft and immediately I lunged forward and freed myself of the dangerous ground. The rocks at launch lost their ominous affect on me. I was free and blasting off. After clearing some treetops, I turned to the left and headed for the gully which was causing most of the cumulus clouds to form. A few hundred yards over was a side ridge with some sun-heated rocks on it, where thermals often bubbled up.

The wind was strong. It pushed me toward the mountain, so I fought to stay a safe distance from the tossing tree tops. Then a gust picked up my outside wing and turned me straight toward the ground. I jammed the control bar down to pick up speed and a second later made a radical turn just before the glider clipped some branches. I worked my flight path away from the mountain and back toward Stormy. From a hundred feet above I watched as he lined up on the path and became airborne. It looked easy from a distance, but I knew he had struggled and that it was a dangerous feat.

Then I watched, paralleling him, as he took the exact same route as I had taken moments before and was sucked into the mountain in exactly the same place I had been. Things happen so fast sometimes, there is no chance to think about them. The fliers body just reacts. He did clear the treetops, just barely. Then he quickly gained control.

Close to the trees, Stormy was in his element, working tiny thermals that dissipated too dangerously close to the ground for most pilots to utilize. He dodged trees and raced through spaces in the forest canopy like a skier on a slalom course. As I was flying safely above the mountain top with hundreds of feet of clearance on all sides, Stormy meandered down into the canyons and joined some Red Tail Hawks who also were dodging obstacles. Soaring with the birds, calculations of elevation and distance needed in order to make safe judgments about each quickly changing situation would have to have been immense. Stormy must have somehow tapped into that vast base of knowledge collected during a million years of bird flight, passed on as genetic material. Maybe after years and years of flying, he had become a bird.

Stormy flew along the treetops and I flew above him several hundred feet. At times, with the high mid-day sun, my shadow would play in the treetops next to him.

He went around a corner of the mountain and I turned in a thermal there. Later, I saw him a mile away, still in the treetops of a ridge I hadn’t explored, far from the landing area.

I saw my limitations. I never ventured too far from a landing pasture. I always gave myself plenty of time to descend. I gave plenty of distance to obstacles. I had remained safe, so far. Even so, maybe I was too timid. Maybe I was not utilizing all of my potential because I was not willing to take any more risks. Maybe I was not recognizing my limits at all, but was instead imagining nonexistent limitations. That day I settled for watching Stormy do things I wouldn’t do and fly in places I would not try to fly.

As we landed later, Stormy was safe and so was I, but it appeared to me that Stormy had taken many, many more risks. Maybe for him they didn’t seem like any big deal.

Indian Valley

When summer came that year, Duke and I drove eight hours to Indian Valley, then eight miles up dirt roads to a shallow, green hillside 2000 feet above the valley floor. Duke had promised me that there would be at least a dozen gliders at a launch site he called “one of the best”, but no other pilots were there. I had hesitated to take this week long camping trip because of the work at home it left unfinished. But now we were there. The wind was blowing gustily between thirty and forty miles an hour. Fir trees on the ridge were twisting and wreathing in the gale. The sound of the wind was spooky. And being alone on this ridge I had never flown from before with a hang glider and an obligation to fly written in the long tire tracks to the launch made me certain that this would be my last day on Earth. I had proven to myself now that I would not be intimidated into driving back to the valley when there was a place to fly from, even though there was no wisdom in that action.

Duke went behind some trees and took a nap out of the wind. I sat upon the windy slope waiting for some idea of what to do. The wind was coming straight up the hill, the way it needed to be in order to launch a glider, and the clear, sunny sky was cheerful enough, if only the wind would settle down and some local pilots would show up. It was a beautiful area, mountain ranges covered with rock and trees into the distance, then valleys checker boarded with farms far below. I was curious what it would look like from the air. There were rock outcroppings on our ridge that might generate thermals to hold us up. The way the wind was blowing, it would be hard to penetrate out to the landing area near a school near the tiny town of Greenville almost invisible in the deep distance. Wind would keep us close to the ridge and , if it was blowing out there as hard as it was blowing across my face, we would probably be blown down wind, over the back of the ridge and into a dangerous rotor of wind pushing down hard toward the ground. I walked over to the ridges back side and sat down in a calm area out of the prevailing wind, in the warm sun. A flag there switched back and forth, breathing in and out like an animal. On the ridge top there was a small area where an emergency landing could be attempted, but with the high winds, it would be very risky. It was surrounded by brush. If one could get a glider to settle behind the brush without crashing, one might walk away, but probably with some damage. There was no room for error. The area was barely more than a wing width from side to side and perhaps a hundred feet long. One would have to approach from exactly the right angle, at exactly the right height. So why was I looking at the place. For me it would be impossible, with my limited flying skills.

I walked over to where Duke was sitting now. He said, “Well the way I look at it, we don’t have a ride back up here to get the car, so, because it’s new to you and you’ll love the view, why don’t you fly and I’ll drive the car down.”

A chill of death came over me. “I’d be crazy to fly an unknown site in these conditions without watching someone who’s already done it.

“Well, it wouldn’t be that bad,” he said ,“ I think the wind’s dying down a bit, or maybe I’m getting used to it. Tell you what, why don’t we set up the gliders behind those trees and hope some company comes along. I can’t believe we’d be alone on a holiday.”

That was at three o'clock. We first saw another car coming up the dusty road at five. The wind had calmed considerably by then.

There were several cars and many pilots and gliders and a party atmosphere ensued. We introduced ourselves to some and Duke shook hands with those who were old friends. One of the local pilots said he’d drive our car down because he’d flown several hours the day before then had gone to a party and was nursing a hangover. Thank goodness for booze, I thought. This explained why the fellowship hadn’t shown up until quite late.

Four hours of summer daylight still lay ahead.

I turned around my glider shortly after the first local had successfully launched into the now steady twenty five mile an hour wind, and I hooked into the hang loop and lifted the glider to look at it’s shape for any clues that I had not rigged it right. It was symmetrical.

So I shimmied it out from behind the trees and into the g

ale. I staggered, facing the wind, with one foot in front of the control bar holding the nose down so the glider wouldn’t blow over backward and be destroyed. Gusts ripped at me but I kept my balance, though just barely. For five minutes I struggled to get to the launch area with the 65 pound glider held on my shoulders, and I was exhausted when I finally lined up to launch.

I could not hold the glider back; it wanted to fly away, so without waiting a second there I ran forward with the nose low, then I eased the glider’s nose up. We sprang off the ground , barely moving forward at all. The glider pitched one way and then the other. Then, fifty feet off the ground the head wind died. Suddenly the glider stalled and I dove straight for the ground. Then the wind blew again hard and I turned ahead again and charged forward, low, just a few inches above the brushy hillside. As I charged forward, the ground moved away. I was tossed up, back and forth, blown at the mercy of the wind. The glide smoothed out as I passed a low ridge top that I discovered was the cause of the wind eddies that had nearly wrecked me.

The wind became smoother and I circled in a thermal until I could look down on the launch. From there the so called top landing area looked infinitely smaller than it had from the ground, between the trees and brush that whipped about in the gale.

I turned to glide along the ridge top to a large rock outcropping that looked like it might produce a thermal. Huge old trees danced in the wind below. I passed a few feet above their slender tops. As I flew over the forest, trying to locate some lift that was better than the ridge compression lift that I now relied on, I found one area where I could rise up slightly to a plateau in the sky. Then there was another area of rising air where I could get four hundred feet above the ridge top and no further. The view from there was spectacular, but I wanted to see more. I circled there for a while, then cut back across the ridge to the other thermal. Then I’d go back to the other one. After an hour the lack of options became irritating, so I thought about landing.

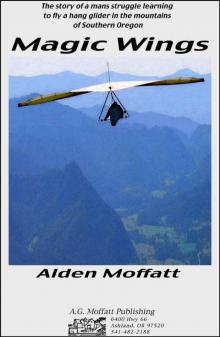

Magic Wings

Magic Wings