- Home

- Alden Moffatt

Magic Wings Page 9

Magic Wings Read online

Page 9

*****

I had toyed with the thought of landing. An hour or more had gone by, and I had found the perimeters of possible travel. I had looked at the world as carefully as I could from my perspective and had locked it into memory as much as possible. The glider was drifting silent and smooth. Then I passed over the landing area and noticing that I had actually gained altitude over the volcanic rocks, I decided that that was a sign that I should stay up a little longer, so I gently turned the glider around. From over a mile up and a mile away, the rim spread out before me from north to south as far as I could see, a huge black stripe on a sage colored landscape.

I closed the gap flying toward it at twenty eight miles an hour nearly silent. Duke was flying way up over the cliff even a little higher than I was. Shadows were becoming long now. Duke was visible, then I would loose sight of him as he turned a corner and exposed the narrow side of his wing to my view. As I neared the cliff again, with the sun behind me, I could see my own shadow, a tiny speck in the shape of a butterfly, move across the cliff face, stretching and shortening as it crawled across every crack and ridge in the black basalt. Having seen about all I could absorb, I began to look inward again, and at the atmosphere nearby. My whole perception of the ground drifted away. I felt around with the glider, for clues, using it as an antenna to bring me information about the invisible world. And in my mind I saw a tiny world, tethered in a universe by invisible forces, a speck as insignificant as I was, occupied by microscopic people who’s only defense against the terror of their insignificance is their denial of their situation.

Free flight, more than any other activity, gives a sustained perspective from where terror can be grappled with. Every fear eventually manifests itself in the mind as one flies. And those fears become insignificant as one is suspended by a string thousands of feet off the ground.

I made a turn in a light thermal where Duke was hovering. We waved to each other and I turned back toward the landing area. I was getting cold, and the hot July evening on the ground was calling me. I was becoming sleepy, and a nap sounded enticing. A small voice inside me suggested that sleeping in the air would not be a good idea at the moment. So I headed out away from the cliff and let the glider drift toward Earth.

Evans Creek

Tweedie found a place to launch on a ridge overlooking the Evans Creek Valley a few years back. He talked with the land owners and got permission to land in a pasture below the launch. The launch itself was on government land.

Not all land owners are interested in having people fly to their property and set down on it. One pilot I know carries a gun when he flies cross country because he had been chased out of a pasture at gun point and had to abandon his glider there until he could sneak back to it at night and carry it home.

Having a great place to launch, where the wind blows just right a lot of the time, right above a great place to land, with the land lords permission, is a rare combination of situations that occur together about as often as million dollar lottery winners.

Tweedie said that the land owner at Evans was friendly. We looked over his field at ten in the morning. “Just don’t leave anything in the field. The owner gets pissed if he’s plowing and runs over an aluminum tube or a glider wheel.”

The ranch house overlooks a huge meadow, a flat, fenced and cross fenced, over a mile wide, next to Evans Creek . That day, no one was home. There was a for sale sign on the house.

“We might not have a landing area here much longer,” said Tweedie. ”I hope the next owner is accommodating.” Then he turned and walked toward our truck, which was loaded down with five gliders and packed with equipment. “We have to hurry. It takes an hour to get to the top of the ridge, and we don’t have much more than that before the wind switches direction. I’ve never seen it flyable here after noon.”

So Duke, Stormy, Tweedie, Butch and myself crammed into one pickup and headed up into the mountains. We left Duke’s station wagon at the house-for-sale.

We bounced up a BLM logging road , went through a gate, for which Stormy carried a key, drove across a land slide, and the track got worse and worse until our forward progress ended abruptly at a huge pile of jack-strawed trees that had blown down across the road. At that point, we were only a few hundred yards from Tweedie’s launch spot. We unloaded ourselves from the truck to assess the situation and decided that it wouldn’t hurt to walk to the launch and see how the wind was blowing, even though the possibility of launching there was bleak. So we all climbed over the pile of logs and walked up the remainder of the road to a little patch of grass surrounded by a brush field, surrounded by huge conifer trees on a gentle south slope. Straight away from the launch, in the distance and far below, the landing field that had looked so huge as we stood in it, looked much smaller.

Tweedie said, ”I say we forget it. There’s no way we’re going to be flying before the wind switches to the north. It’ll take an hour just to get the gliders carried over here and get them set up. Then it’ll be after noon and I’ve never been able to launch here after noon.”

“Come on Tweedie. Quit whining like a little puppy dog,” said Duke. “The wind’s perfect and it looks like it’s going to stay that way.”

“This looks like it’s going to be quite a bit of work,” said Stormy. “I’ll carry my glider over here, but I’m not helping anyone else. You’re on your own.”

“Well, I guess I can do this,” I said. “The wind does look perfect. It would be a shame to drive all the way here and then drive back down.”

The launch area was sloped just a little steeper than the bunny hill at Emigrant Lake. The landing field looked like an easy glide, even if there was no lift to the air. We were two thousand feet above the field and two miles from it, the same situation as at Woodrat Mountain. This mountain looked gentle and unintimidating. The thick forest of tall old trees looked deceptively soft and fluffy. I found myself almost enthusiastic about getting airborne.

I was the first to walk back down the road to the truck. There was a muddy cut bank on the down hill side of the road where it would be very tricky to carry the gliders, but it was the only way to get the gliders around the pile of broken logs blocking the road.

Tweedie said, “You guys are nuts. We’re gonna get all set up and then were gonna carry all this crap back to the truck and load it up for the long drive down the mountain.”

“You’re such a pessimist,” said Butch. “I didn’t come here all the way from Roseburg just to listen to pessimism and drive down the hill. I don’t care how bad it gets. I’m launching, even if the winds blowing straight across my back.”

“Well I’m not that nuts,” smiled Duke. “I’ll just take it as it comes. If it doesn’t work, it won’t be any worse than all those trips to the coast with Tweedie, where we drove six hours and then got skunked.”

“That’s right Tweedie,” said Stormy. ”How come it’s OK to sit in a car for six hours and get skunked over and over, but you act like a little girl in a pink dress about this today.”

“Well OK,“ huffed Tweedie. “I’m no pussy. But I’m telling you, this is looking pretty bleak.”

So we shimmied the gliders, one by one, around the log jam and then shuffled the sixty five pound gliders up the road to the launch, puffing and panting in the late morning sunshine. Each of us made three trips to the truck to get equipment, then we hurried to set it up. By the time all the gliders were about ready to fly, that perfect, up slope, up the launch thermal wind rising off the valley had become twitchy and occasionally wind puffed from behind the mountain.

The set up area was small, so we all had to wait for the glider in front of us to be moved before we could turn around the next glider and line it up on the launch slot. But Butch was ready and eager to fly first and he decided to try to carry his glider, with him hooked onto it, around the tiny bit of space between our wing tips and a brush patch. So, while I was completing my own set-up, trying to remember everything that needed to be done, Butch was stumbli

ng around very close to delicate glider parts, occasionally tripping or snagging on something.

“Sorry man,” he said. “Oops.”

“Jeez,” Stormy shook his head in disgust. “For crying out loud. Can’t you wait for five minutes!”

“I’m not going to get stuck up here and have to drive back down with you slow pokes,” Butch said. He hastily lined up on the launch and as the wind made a red survey flag flutter lightly up the hill, a few minutes after noon, Butch ran as fast as he could and barely became airborne. We all stood in amazement watching, trying to learn whatever we could about the air. Butch gained a little altitude.

“Turn,” said Tweedie. “Man what is he doing? He’s gonna fly right through the lift.”

“It certainly looks like he’s hunting for some sink,” said Stormy.

“Look, I think he’s found some now.” Duke grinned.

“Watch him turn now,” said Tweedie.

“Ha,” said Duke. “He’s a zero.”

Butch turned as soon as he hit a sink hole.

“Well, there’s no point in watching that guy for expertise,” said Stormy as he turned to his glider and started putting on his harness.

I watched as Butch smoothly slid through the sky toward the landing field. Then I grabbed my harness and struggled into it.

“Well, it beats driving down,” said Duke.

I was next in line. The day and the launch seemed so docile that I didn’t even consider being nervous. But as I ran as fast as I could down the launch hill, my glider was barely lifting off my shoulders, barely flying. I realized then that I had not been paying very careful attention to the conditions. Was the wind blowing up the hill when I had started running? There was nothing I could do about it now. I ran out of room to run. The glider was nearly stalling, barely lifting me over the bushes. My feet, with my knees bent back, were dragging on the brush. Because I was so close to the ground, there was no way to speed up and develop more lift. So I plundered along, sinking with the slope of the hill side for a long few seconds, barely surviving. The trees below me got closer and I knew that I had, at best, a one in two chance of hitting them. But that day, as on many days, I was lucky. A gust of wind plowed into my face. The glider lifted up and I became safely elevated. I turned toward the invisible thermal that Butch had flown through. It was coming up a heavily timbered gully that was progressively steeper as it rose up the mountain. I heard the gliders wings tighten and the control bar became tensioned like an instrument string. Knowing I would be laughed at for not turning in the lift, I made a tight turn away from the mountain. Unexpectedly I fell out of the narrow thermal and lost more than a hundred feet of elevation.

I tilted my head up as I passed well below the launch. As I expected, Duke, Stormy and Tweedie were watching me, scrutinizing my flight. I looked the other direction. With just the loss of a hundred feet of elevation, I began to feel uncomfortable with the distance to the landing area. The trees no longer looked fluffy and gentle. I could see the hard ground far below the tree tops; I was very close to their green, tender top branches.

I made a careful turn out toward the valley, trying not to loose any more elevation. And then I followed below Dave's flight path. Butch was now circling close to the landing field.

This was a game, I thought. and I was not winning it today. Gliding was about reading the subtilties of nature accurately. I had not paid enough attention because I was relaxed before I had launched. Now I was humiliated at best, or worse, I would become one of the tragic stories that pilots pass down through the generations. The consequences of this game were real. The gossip would be worse than the actual crash. That was becoming obvious to me.

I followed straight to the landing area with my tail between my legs, whimpering. There was no lift to speak of as I flew close above the beautiful old growth forest . The angle of the mountain slope must have been identical to the angle at which I was descending through the air because the forest never got very far away.

I arrived at the old homestead beside the creek two hundred feet above its roof top. I was aiming for what I thought would be the best approach for landing. I made a slow turn just above the roof top when a strange wind caught me. The wind was blowing gently in my face, but it seemed to be lifting the rear of my sail upward, forcing the nose of the glider down. The effect was erie. My forward motion came to a halt. The glider was rising up slowly, but I felt I was balanced on a very, very small thermal coming off the roof and the position felt treacherous. I thought at any moment I might be flipped over. Despite the lifting effect, I decided that I was in danger, so I jammed the control bar over and made a steep turn toward the field.

Butch had already landed and had just moved his glider out of the way. I glided toward the wind flag, which was blowing away from me; the wrong direction. I saw fences that divided the field into little squares. As I passed over one fence, flying with the wind at my back, I dropped uncomfortably close to the ground. I didn’t want to land in that direction. The tail wind would push me over when I tried to settle to the ground.

But there was no room to turn around. If I pulled in on the control bar and raced toward the ground right then, I thought, I could have a minor crash landing, another embarrassment. If I waited another few seconds and tried that, I would slam into a barbed wire fence at the far end of the field. I couldn’t make up my mind what to do, so I did nothing. I kept going in a straight line until it was too late to take either choice. I was thirty feet off the ground, headed toward a marsh that was beyond the fence wire. It appeared that there were no options left as I passed directly over the fence. But the air surprised me. I wasn’t loosing elevation as I drifted low over the field. So I decided to try a very flat turn very close to the ground. One wing tip nearly touched the fence as I made a wide semi circle. I ground my teeth together until the turn was complete and I was faced into the wind with the whole empty field in front of me. I breathed deeply and smiled as I cruised forward and landed perfectly, next to Butch.

Butch acknowledged that the air was weird and that he had some tense moments too. Butch was not smiling. “I don’t think I need to come here again,” he said.

Stormy swooped down from the sky shortly. Together on the ground, we all watched Tweedie glide higher and higher until he and his wing disappeared into the blue. “Son of a bitch,” said Stormy. He grabbed his ham radio after a few minutes. “You better get down here Tweedie or you’ll miss your ride.” He looked around. “You guys seen Duke?”

“No,” Butch and I both replied.

“I wonder what’s going on?” Butch sounded concerned.

“Hey Tweedie,” Stormy said to the radio. “What’s up with Duke?”

“I guess the wind crapped out and he couldn’t launch,” the radio crackled. “Last I saw, he was carrying his glider back to the truck.”

“Poor guy,” said Stormy.

“Hey,” said Tweedie over the radio. “This is great flying up here. I’m almost at seven thousand feet. Sure am glad you talked me into doing this today.”

Stormy growled and turned off the radio.

Walker Mountain

Walker Mountain, according to Duke, was not a favorite place to fly because, as he said, “You never know where you’re going to land. The main LZ is a stretch for any glider and the bail-outs are all weird. There’s a gun club, shooting range where we have to land sometimes, and you can hear the bullets fly while you’re circling overhead. You just have to hope they quit shooting before you set down.

“Then there’s the airport. But one time I landed there and a private jet barreled in along side me and just about threw my glider into the maintenance building. You wouldn’t believe how pissed I was, and, ’you gotta be kidding’, I thought, as a big, superstar karate guy sauntered down the steps from the plane all dressed in white. I decided it wouldn’t be such a great idea to yell at him about his lack of respect for other kinds of pilots.

“ Or you might end up twenty miles down the freeway,

” continued Duke, “landed in the center divider with no ride home but with a paddy wagon waiting to take you to jail.

“Anyway, here’s the main landing area,” he said as we drove onto a big flat field. “And there’s where we launch.” He pointed to a red rock mountain in the distance. “If you don’t start climbing right away after you launch,” he said, “ don’t wait. Come straight out to this field. That’s the only way you’ll cross the freeway and make it here safe.”

Tweedie and Stormy pulled in right behind us and we all got out of the vehicles. We loaded all the gliders on Stormy’s truck.

Stormy walked out to the end of the field and stuck a wind indicator flag in the ground. Then he walked a little way and put in another flag. Then another. When he got back to where we were standing he said to me, ” The wind’s pretty switchy around here. I don’t trust it for a second. I’ve set up for a landing a bunch of times and had the wind switch and crap out my landing. Sometimes you’ve got to turn all the way around, with twenty feet of elevation, to land into the wind because the wind switches all the way around. Pay attention to the flag.”

Tweedie was just along for the company today. He had volunteered to drive Stormy’s truck down from the launch. Tweedie was the original flier at Walker Mountain. He had discovered the launch and had gotten permission to land in the field at the base of the mountain. Tweedie had flown all the way from Walker Mountain to Woodrat on occasion, a flight of over thirty miles. Regularly, he landed half way there, on a department store parking lot in Grants Pass.

Tweedie was the local, classic hippy flier. He was middle age but still wiry and out spoken. “I’m gonna call you Aldo Nova from now on. That’s your nick-name,” he said to me. Remember that rock band in the seventies. I wonder what ever happened to those guys. Aldo Nova.” He looked at Duke and Stormy looking for their approval while pointing a finger at me. “Don’t you think that’s appropriate?” He put his arm around my shoulder. “Nova,” he explained. “ Something up in the sky that explodes in a big way.”

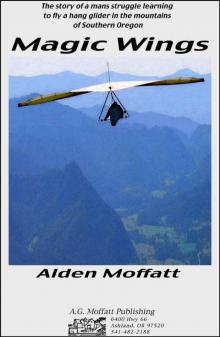

Magic Wings

Magic Wings